I’m sure I missed some beautiful country, driving through those hours when coyotes and criminals feel safer with the dark, though I passed a dead coyote along the rim of the San Luis Reservoir.

I arrived in San Jose to find that the gallery exhibiting Barron Storey’s work opened at 10, which left me time to be restless. 10 came and went and the gallery remained closed, so I lunched at a Thai place, returned to the gallery, and still it was closed. I called them, left a message. I emailed them, said I was right outside their door. I had come all this way, for art’s sake! Around noon they emailed back and said they had opened. By then I’d received a $40 parking ticket while straying along the streets twelve minutes too long, not paying attention.

It was worth the wait, and the ticket, too.

I bet most of you have seen at least one illustration of Storey’s, if you don’t have it on your bookshelf. The particular piece I’m referring to is the paperback cover of Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Here is the back cover art, minus the typography.

Barron is the most incredible draftsman ever. Here is one of the earliest works I kept of his.

He drew this cover in a Time magazine office based on a witness’ description of Howard Hughes over the phone, the night Hughes died. An amazing portrait considering there were no photos of the reclusive Hughes that were less than 20 years off date.

I walked into the gallery, Anno Domini.

Just as there are some aspects of life we have difficulty facing, so it was with the subject of this exhibition, titled Suicide. I viewed it as a fellow of humanity and as an artist, both perspectives impacting me. As with most art, a reproduction conveys little about the original. Seeing Barron’s art up close and intimately, you see through layers, literally and figuratively, trying to comprehend where it all comes from and how deep it goes. He opens his soul to you; you glimpse his torments. And, if you can look beyond the subject, you are fascinated by his intricacies and you see how they fascinate him.

I learned that this particular subject was his torment of torments. The first piece was one he drew from life. Death, rather: it was

of his mother lying in a hospital bed after she swallowed rat poison. Enough

rat poison, the doctor told him, to kill an army. Barron was 23.

For this collection of … I will call it work

for the purpose of simplicity, though it involved not only sweat, but

blood and tears … Barron had already been immersed in the

subject for years: besides his mother, his uncle, Barron’s ex-wife, and a close friend took their own lives. There were over 70 works. Artistically, there was so much to learn by studying them I perused the exhibit three times.

Barron divided the art into clusters. Alongside each cluster he wrote in pencil or pen directly on the wall, defining a particular phase or sub-theme of the work. The cluster he numbered 5 reads What Good Am I? Cluster 7 represents work he did involving interviews he’d had with those who knew suicide victims. The cluster of work in 8 conveyed how the project itself affected him. I sensed it was near catastrophic.

The brochure for the exhibit reproduced Barron's remarks:

"Started asking people: Did you know anyone who committed suicide? So many did. Made drawings about each one. They piled up. Show them? Ugly ... Ugly subject. Ugly feelings. What have I done? OK. The question is: What did they do? And why? Pages and pages of journal drawings ... Lord, let it be over."

To be cont.

for dreams and death chants, part one, click here

I never did tell you about my California adventure. Not that I had only one — I was born and raised in California and my adventures were many, like the time a bear stole my backpack high in the Sierras, or when the hood (the bonnet, in Britspeak) flew off my ’59 Jag on the Pasadena freeway, or when I nearly died from a bee sting …

But on a more recent occasion, while visiting family and friends, I was headed to the Central Valley from Long Beach, and had become so sick with a respiratory flu I wanted to clear my head and body in the wilds. I wanted clean air and uncluttered space.

It happened fortuitously. I missed the right fork in the freeway, literally, which put me on the 5, still heading north but a bit closer to the coast. On this stretch the country is wide open, dusty, and uninviting. Deciding to postpone my stay with my octogenarian mother (not wishing to compromise her health), I proceeded.

I saw that Pacheco State Park was a couple of hours away. I imagined trekking through dry grasses, over hills studded with oaks, sketchbook-ready, inspired. A picture formed in my mind of a lone live oak on a hill, spreading like a Rorschach test over the barrenness. I knew how I’d render the leaves; I knew how I’d render the grass.

My fever rose so high at times I felt the fringes of delirium.

As I drove further north and west, I recalled a Robin Williamson song.

Purple clouds turn scarlet in the setting sun

Where sagebrush turns to live oak and the white-tail run

The air is cool as music when the day is done

And God paints the sky above Pacheco

Driving all day up the San Joaquin

Turn west again, up through Pacheco

Through the blue hills back of Santa Cruz we're rolling fine

Where red-tailed hawks go circling like the waves of time

Lovers and friends will meet again around red Sonoma wine

When God calls the night above Pacheco

I drove all day and into the evening, arriving at a place I thought was near Los Gatos — The Cats (named after the mountain lions and bobcats indigenous to the region) — where John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath and violinist Yehudi Menuhin lived as a boy. But, getting sicker by the mile, I pulled into a KOA and sat for a moment. It was early evening and I was in Los Banos — The Baths. I hoped to rest a few hours, shower, and get back on the road to somewhere more scenic, expecting to be well enough to draw my dreamscape.

My fever dropped, my appetite returned, and I found a Panda Express near a truck stop. To get to the door I had to wade through a whine of feral cats, begging with their hungry tongues and their hollow eyes. They were all the same dirty beige. As I ate I watched them watching me, with a picture window between us. I could eat only part of my meal, and cracked open the fortune cookie, which prophesied:

You will meet an old friend.

Feeling worse again, I returned to the KOA, registered at the desk, and pulled into a spot to sleep. More cats surrounded a dumpster in the distance—surreal, ghost-colored cats, all the same dirty beige. My fever went up again and I sat there in a sweat. I decided to take a shower. On the way to the showers I passed the community room, a large windowed porch off the main office. Under cold, harsh lights people not much older than I shared a potluck meal, camaraderie, and card games. What a ghastly way to spend your life. But each of us must find his own happiness. They all seemed happy. In the mens room I saw a phantom in the mirror that looked too sick to shower, so I went back to the car. Perhaps in the morning I’d feel better. My fever would not quit. The night was a continuous John Fahey death chant. I sat and gazed at the dumpster. All the cats were gone but one, a sentry, perched on the lid, watching for rats. I shared my misery with it.

Around 4 am my fever broke. I was ready to get back on the road. I headed for the showers again but the door was locked. After retrieving the code from my car, I still could not get in. I lose patience with such things. The code had been hastily jotted down by the woman behind the desk, and after I realized the 8 was actually a 3, it was too late. By the time I had finished punching numbers I’m sure I’d re-programed the lock. I ended up in a posh outhouse, washing my head in the sink and taking what the locals back where I live call a sponge bath (from an earlier time when wells went dry and you had to conserve), avoiding the black widows all the while.

Enough. I was ready to see the sun, see the sea. Though my fever had dropped, I coughed like a dog. Changing my plans, I headed for San Jose. There was a gallery that displayed the works of an instructor I’d had during my Art Center days in Pasadena. Barron Storey. He’s in his seventies now. I had to see what he was up to.

for dreams and death chants, part two, click here

cover art from a John Fahey album

My Writing Process

A writer friend and critique partner, Brian Rock, has invited me to an ongoing blog tour that includes many other writers. Here are my answers to some frequently asked questions.

What am I working on? Hans Andersen’s Ghost, a magic realism middle grade novel. And a rough draft for a companion book to follow The Dragon of Cripple Creek. And when the ideas come (which have been often, lately) a few picture book stories. And, and, and …

How is the work different from others in its genre? First, everyone is “different” if they’re tuned in to their own uniqueness and voice. I don’t follow trends. My primary inspirations come from within. In the case of my work in progress, I’ve added the imaginative works of Hans Christian Andersen (minus his excessive sentimentality), as a source of material. My works tend to concentrate on the private world of the lone child, rather than on a communal or social circumstance. Also, how I say it is as important as what I say.

Why do I write what I do? Passion. Playing with words and ideas. The joy of sharing. Through my work I can say, “Look! See! Discover! Wonder!” As I present matters that catch my mind and eye and heart, I want it to be as enjoyable and purposeful as I can make it, something that both captivates and reveals. I prefer to use magic realism, merging make-believe with the real, because life is so full of mysteries and hidden truths. I especially like contrast: the confident with the fearful; the meek with the mighty; ancient with modern; magical with mundane. It’s kind of a literary chiaroscuro. And if my stories awaken something within the reader, that’s rewarding.

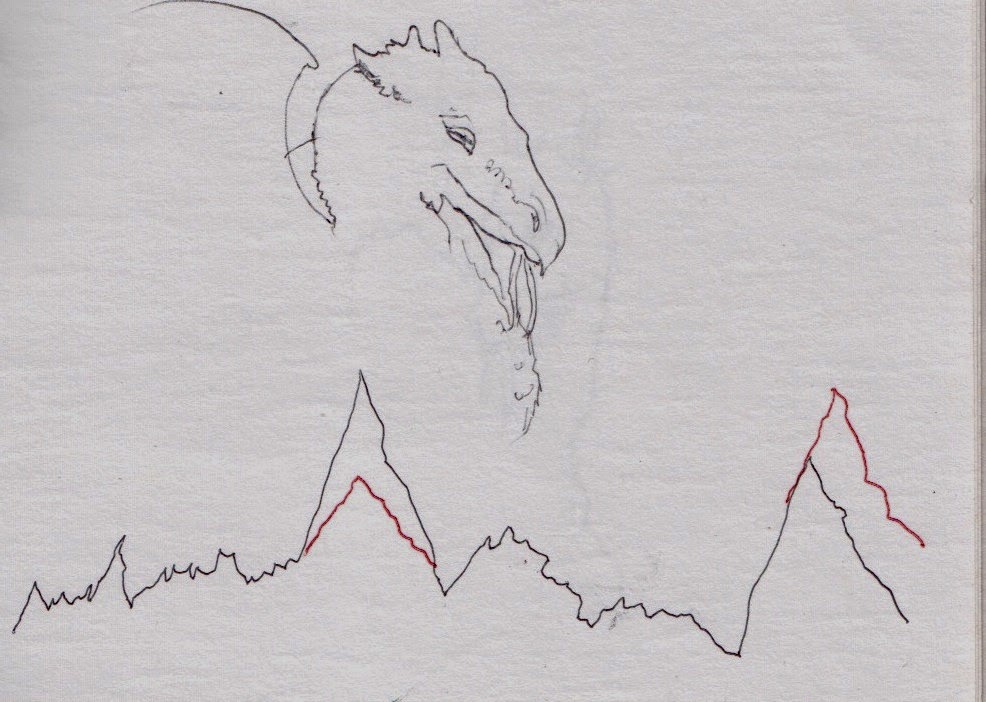

How does my writing process work? It begins with an idea. Sometimes the idea comes from a desire to write about a particular situation—say, what happens when a child’s imagination is suppressed—or an image in my mind, or a blend of randomness and logic. For The Dragon of Cripple Creek, it began with wanting to put a dragon in North America. What naturally followed was to write a new American tall tale, to juxtapose something ancient with today’s world. Dragons are not really my thing, and I wanted to stay clear of the dragon stereotype. If anyone were to breathe fire, it would be the girl who discovered the dragon, not the dragon himself. The idea was appealing enough that once it held me I couldn’t let go until I had seen it through. For Hans Andersen’s Ghost, it began with an image in my mind: a boy in modern Copenhagen who dons Andersen’s old top hat to find himself in Andersen’s imaginary world, a place no less perilous than his own. I believe Andersen’s tales run the risk of losing relevancy, if not vanishing altogether. This is my way of introducing him in a new way to a new generation. (How many know that it was he who wrote "The Little Mermaid," and not Disney? How many know she dies in the end ...)

Being a visual artist, I often do a sketch in anticipation of the work.

Once

I like an idea enough to pursue it, I begin by writing the first lines

to see where it goes and to get a sense of its voice. These beginning

lines feed what will follow. It’s a matter of creating something of

quality and uniqueness that inspires me to continue. There comes a time

where I adjust and organize the action to a satisfactory climax, but

I’ve found that if my beginning isn’t just right, there’s no need to

continue, because everything flows from that.

The mountainous plot chart I sketched for The Dragon of Cripple Creek to help me see where the high action points were occurring. After rating them as you would elevations in the Rockies (which is where the story takes place), I concluded that the mid-point climax was greater than the final. I had to revise both, indicated by the red lines.

So it’s the beginning where I spend the most time and concentration. It becomes very intense; it works into my dreams. The beginning, which is about the first 25 pages, also shows me a glimpse of theme or themes, the true why of that particular work, and once I have a clearer sense of what I’m saying, I can write with more certainty. More thought goes into this portion than actual writing does. I will then work on the end until I’m satisfied with where it’s going, and the rest involves tying the two together. I begin as an explorer, and become a discoverer, a surveyor, an engineer, an architect.

As to daily word count, I don’t keep track. Some days I may write hundreds of words, even a thousand, some days only a few. It really depends on where I am in the process. Some days I pace and think and talk it out of myself.

Part of the process includes subjecting my work to the fresh eyes and minds of a critique group (in my case, the Richmond Children's Writers), a valuable resource for any serious writer.

As to the physicality of it, I sit at my table and torture the keyboard, with a cup of espresso nearby and the chaos and calm of nature outside my window.

Literature not only allows us to hear language differently from the everyday,

it makes us see life in ways we otherwise would not.

monotype © 2014 by Troy Howell / click on image to enlarge

writer’s block

he dips his pen

into the void

and draws out nothingness

he tries again,

again, again,

and

artwork & poem © 2014 by Troy Howell / acrylic, wax, crayons, ink, on rag board